:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/easy-origami-crane-instructions-4082282-32-5c59e871c9e77c000102d1e6.jpg)

(© Doi Emi) A Paper Crane for Pearl HarborĪ tiny paper crane less than the size of a thumbnail, folded by Sadako herself before her death, is on display at the Pearl Harbor Visitor Center in Hawaii, one of the recipients Sasaki has chosen for the few remaining cranes that his sister made. Even his necktie sports a paper crane motif. The walls of Sasaki’s Fukuoka Prefecture barber shop are decorated with senbazuru sent to him from all over the world. Sasaki has set up a nonprofit organization in Japan called the Sadako Legacy, and is engaged in peace activities, which include giving talks and using the remaining paper cranes left by Sadako. We asked Sadako’s brother, Sasaki Masahiro about the increasing globalization of origami cranes. The Children’s Peace Monument and booths filled with senbazuru offerings. Sadako’s story was later taken up in numerous children’s books and school readers, and has become familiar to children around the world. Junk, a Holocaust survivor himself, said he was moved by Sadako’s attitude to life, her intelligence, and her consideration for her parents’ feelings. In 1956, the Austrian journalist Robert Junk visited Hiroshima and introduced Sadako’s story to the world in his book, Light in the Ruins.

Indeed, the story of Sadako and the thousand cranes may be better known abroad than it is within Japan itself. Some 10 million cranes from around the world are offered here every year. The Children’s Peace Monument in Hiroshima’s Peace Park-a figure of a girl with arms outstretched, holding up a golden paper crane-is said to be modeled on her. Sadako was a keen runner, and in the belief that she could recover and return to normal life, she continued to fold from 1,300 to 1,500 paper cranes while in her hospital bed. She developed leukemia at the age of 12 and died after an eight-month battle with the illness. Sadako was just 2 years old when the atomic bomb was dropped on her home town, Hiroshima. (Courtesy of Sasaki Masahiro and the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum)īehind this global recognition of the power of paper cranes lies the story of Sasaki Masahiro’s younger sister, Sadako.

When 12 boys and their soccer coach were trapped in flooded caves in Chiang Rai, Thailand, in June 2018, the classmates of one boy folded 1,000 cranes in three days to pray for the group’s safe return. As the crane is a symbol of long life, strings of 1,000 paper cranes, or senbazuru in Japanese, are often offered as a get-well gift expressing hope for a person’s recovery, as a sign of support for natural disaster victims, or encouragement for sports teams.īut paper cranes are starting to become known around the world as a tangible form of prayer for peace or a way to show of support for people facing difficult challenges.

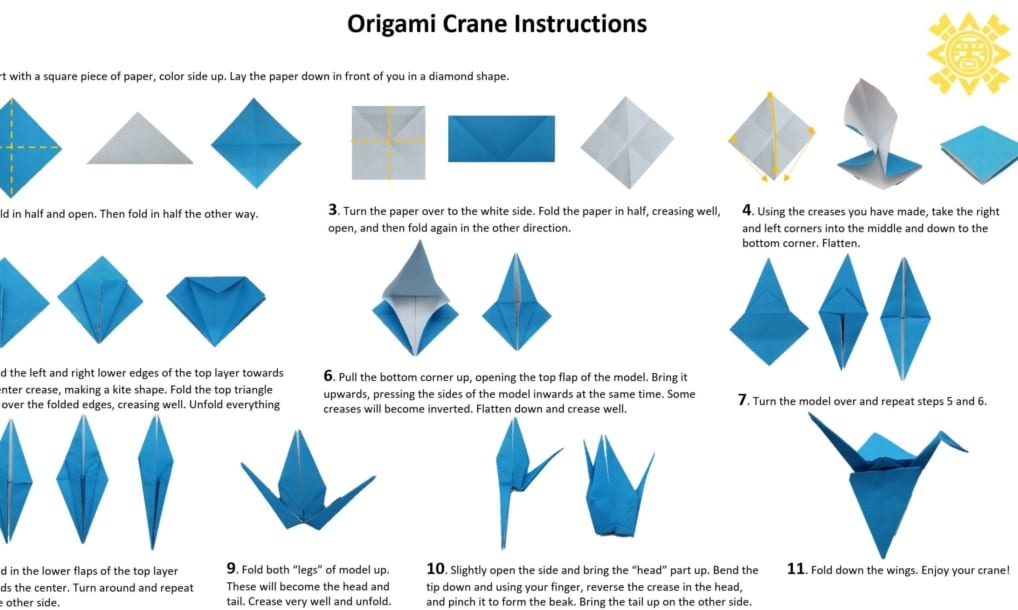

PAPER CRANE ORIGAMI HOW TO

Origami, the art of folding paper to make decorative items, is a common indoor entertainment in Japan, and most people learn how to fold an origami crane in their youth. President Barack Obama and Caroline Kennedy, then US ambassador to Japan, folding paper cranes during the President’s historic visit to Hiroshima in 2016.(© Jiji Press) I sensed from those folded cranes both his humanity and that message.” Obama later donated two more paper cranes to the second atomic bomb target, Nagasaki. “Even though he couldn’t give an apology as President, I think he was delivering a personal message that he was sorry. Sasaki Masahiro, author of Sadako no senbazuru ( Sadako’s Thousand Cranes), was amazed when he heard that the president had made the cranes himself. He brought with him four paper cranes that he had folded himself. In May 2016, Barack Obama became the first sitting US president to visit Hiroshima, site of the world’s first atomic bombing in 1945.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)